Until recently, my formal beverage tasting experience has been singularly focused on beer. I’ve judged beer in competitions from South Africa to Virgina and held countless semi-formal tastings with friends and family. But, although I roast my own coffee beans at home, I’m a newbie when it comes to professional coffee cupping.

My first official cupping was just last month when I visited the Asorcafe coffee lab (above) in the small town of Pedregi, in the Cauca region of Colombia. The lab technicians were experts, as were my companions from Peace Coffee and Higher Grounds, so I had good coaching that helped prevent me from dribbling coffee down my chin. I did, however, begin the cupping while wearing a cowboy hat which Jody from Higher Grounds suggested I remove so as to avoid knocking over glasses as I bowed my nose to the grounds.

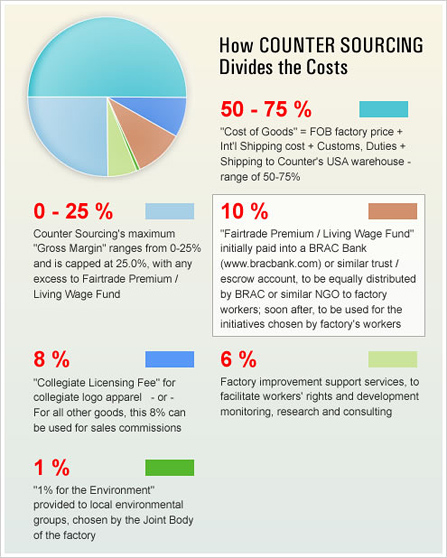

This morning I attended a free cupping at Counter Culture’s lab in the Adams Morgan neighborhood of Washington, D.C. (For background on Counter Culture’s “direct trade” business model, read my online conversation with Kim and Peter from Counter Culture and my other recent post about the chat I had with folks from Intelligentsia, the company that trademarked the term Direct Trade.)

Here’s a primer on the tasting procedure and a report on the three coffees we cupped this morning.

The Cupping Ritual

Our host, Ryan Jensen, Customer Relations, prepared by lining up a set of about ten 8 oz. glasses for each of the three coffees. He scooped about a tablespoon of grounds (13 grams to be exact) into each glass. It’s important to cup several glasses of each coffee in order to avoid mischaracterizing a whole batch based on just one cup. A single glass can exhibit a defect from one bad bean but the rest of the batch might be flawless. Once the glasses were filled with grounds, we were armed with pens, clipboards and cupping forms. Silence and furrowed brows indicated that the ritual was about to begin.

1. Moving from glass to glass, we sniffed and noted the fragrance of the grounds.

2. Then Ryan poured 8 oz. of hot water into each glass. Going glass to glass again, we smelled the aroma of the steeping coffee.

3. We were given small paper cups and large spoons with deep basins. We used our spoons to once again move down the line of glasses and “break” the layer of grounds floating on top of the coffee, noting the fresh burst of aromas released by this technique. The grounds were then removed from the glasses.

4. For the final gauntlet of grounds, we dipped our spoons into the glasses and raised the samples to our bowed heads. Using our lips, we slurped across our tongues, aerating and roiling the coffee throughout the mouth, saturating every taste receptor from front to back, top to bottom, and side to side. After each swish, a few of the cuppers opted to avoid ingesting too much coffee by spitting the samples into their cups. Most, including me, chose to go whole hog and swallow every ounce.

In this last step we actually tasted the coffee, noting brightness, flavor, body, and aftertaste. In beer tasting terminology, brightness is similar to crispness. A bright coffee is snappy and clean like a pilsener, whereas a less bright coffee is mellow and smooth like an ale. (I’m generalizing here, don’t take this beer comparison too far because the exceptions will just make it confusing.)

Flavor is what you taste. Anything goes – the point is just to recognize all the flavors you can identify. Flavor can be intense or subtle, direct or nuanced, complex or one-dimensional. I relied on one of the handy tasting wheels Ryan had distributed in order to help connect what my taste buds were experiencing with what my food-memory has stored in the recesses of my mind. Body can be full or thin. Going back to beer, Bud Light is thin-bodied and watery, while imperial stouts, barleywines, and double IPAs are rich and robust. Aftertaste is how any flavor lingers on the palate or cuts short and clean.

Flavor is what you taste. Anything goes – the point is just to recognize all the flavors you can identify. Flavor can be intense or subtle, direct or nuanced, complex or one-dimensional. I relied on one of the handy tasting wheels Ryan had distributed in order to help connect what my taste buds were experiencing with what my food-memory has stored in the recesses of my mind. Body can be full or thin. Going back to beer, Bud Light is thin-bodied and watery, while imperial stouts, barleywines, and double IPAs are rich and robust. Aftertaste is how any flavor lingers on the palate or cuts short and clean.

Here is a summary of my tasting notes.

Coffee #1: Peruvian from Valle del Santuario, Ignacio

Representative of its region, this certified organic, shade grown coffee is an everyday cup, the equivalent of what beer drinkers call a session beer such as an English bitter or American amber. Milk chocolate and brownies dominated the fragrance. Sweet, roasted peanuts appeared in the aroma. The break released leather and malt. As a routine morning cup, the brightness was light and mellow, with an earthy flavor, mild body and little to no aftertaste.

In one word: quaffable.

Coffee #2: Kenyan from the Gaturiri and Nyeri regions (auction lot #4486)

Coffee #2: Kenyan from the Gaturiri and Nyeri regions (auction lot #4486)

After the cupping, the participants unanimously requested this one to be brewed as our cup to savor during the post-cupping discussion. Because of the Kenyan national coffee system, direct, fair trade coffee buying relationships are nearly impossible. So, although this coffee’s region of origin is known, its exact farmers are anonymous. Furthermore, it is neither organic nor shade grown. Damp earth and dark berries and fruits in the nose made way for roasted nuts at the break, followed by a bright, tangy grapefruit, tangerine, spicey cinnamon flavor. While it was perhaps the most rewarding cup of the three, the medium body was just shy of the strength needed to counter balance the punch of citric acid that lingered in the finish.

In one word: conversational.

Coffee #3: Sumatran from Gayo, Aceh

Certified organic and shade grown, earth and smoke came to the fore throughout this complex cup from the damp forest lands of Sumatra. The nose was rough, like roasted chestnuts, pungent and acrid, with a full-bodied musty, tobacco-like flavor and lingering hide-like aftertaste.

In one word: comforting.

Proof that Beer and Coffee Are the Best Companions

After the tasting, I thought it was only fair to let Ryan know that the reason I attended was that I am an author and I’m conducting research for my next book. He replied that he had just started reading Fermenting Revolution two days ago. I’m hoping to make the Counter Culture lab a place for repeat visits in the coming months of research. I’ll have to treat Ryan to a beer sometime as thanks for his free educational cuppings.

Posted by beeractivist

Posted by beeractivist

CupCoat. Why is everything twowords combined into one these days?

CupCoat. Why is everything twowords combined into one these days?